CMBV/Opéra d’Avignon/Opéra de Massy: Amadis (Lully)

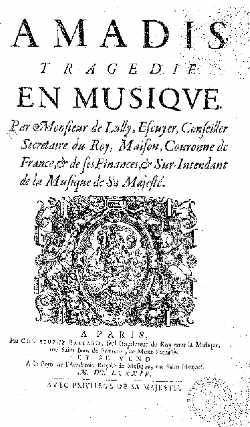

Amadis, tragédie en lyrique in a prologue and five acts, by Jean-Baptiste Lully [1684], libretto by Philippe Quinault, after Essart’s translation of Los quatros libros del virtuoso cavallero Amadis de Gaula by Garci Rodriguez de Montalvo (c.1492).

Cast: Cyril Auvity (Amadis), Katia Velletaz (Oriane), Isabelle Druet (Arcabonne), Alain Buet (Arcalaüs), Edwin Crossley-Mercer (Florestan), Dagmar Šašková (Corisande), Hjördis Thebault (Urgande), and Arnaud Richard (Alquif / Ardan-Canile)

Corps de ballet: Ballet de l’Opéra-Théâtre d’Avignon et des Pays de Vaucluse (solo dancer: Robert Le Nuz); Chorus: Les Chantres du Centre de Musique Baroque de Versailles; Ensemble: Orchestre des Musiques Anciennes et à Venir, conducted by Olivier Schneebeli.

Directed by Olivier Bénézech, with dance choreography by Françoise Denieau & Robert Le Nuz, set design by Gilles Papain & Olivier Bénézech, costumes by Frédéric Olivier, lighting design by Philippe Grosperrin and still & video images by Gilles Papain & Marie Jumelin. Co-produced by Centre de Musique Baroque de Versailles, Opéra-Théâtre d’Avignon et des Pays de Vaucluse, and Opéra de Massy.

Over past 25 years or so, French audiences have been able to witness a gradual process of rehabilitation in one of their most important composers, as one by one Lully’s operas have been taken off the shelves and re-staged, starting with Jean-Marie Villégier’s production of Lully’s Atys that William Christie directed, first in Paris in 1987, and then New York two years later. I was lucky enough to see the latest step in this process, with this new production of Amadis, staged in Avignon and Massy a couple of weeks ago. With our love of chronology, and the insistence that opera is first and foremost an Italian art-form, it’s usual to put Claudio Monteverdi at the top of the list of early opera composers, yet only three of his works have survived, and none of them were performed after the 1640s, until the 20th century. The operas of Jean-Baptiste Lully, on the other hand, are only obscure nowadays because of the enormous shifts in fashion and politics that took place in Europe after the 1790s. Previous to that, Lully’s works were central to the repertoire and understanding of opera in France, and were restaged and adapted right through the 18th century, making Lully the first major opera composer. No understanding of opera history can be complete without him, and yet it is frustrating to see how little recognition his work still gets even now.

The partnership of writer Philippe Quinault and composer Jean-Baptiste Lully led to the creation of a new genre, the musical tragedy (tragédie en musique) in the 1670s. This mode of theatre brings together dance, sung poetry and classically-inspired drama in a way that has only occasionally been emulated since. Of the 13 operas that they created together, Amadis (1684) was the first to be based on a chivalric romance, rather than classical mythology, and it was followed shortly after by two more: Roland (after Ariosto’s Orlando furioso) and Armide (after Tasso’s Gerusalemme liberata). The form of the chivalric romance is best known to us nowadays from the medieval tales of King Arthur, with knights in shining armour heading off across the countryside seeking to prove their glory and honour by winning battles and saving damsels in distress. It’s a bit more involved than that, but you get the idea.

Amadis, the knight in question, is desperate to regain the love of his beloved Oriane, who thinks he has been unfaithful to her.

Meanwhile, the evil pair of Arcalaüs and his sister, the enchantress Arcabonne, want to destroy Amadis in revenge for him killing their brother. They entrap Oriane, as well as Amadis’ friend Florestan, and reel him in. The entrapment takes place in an enchanted forest, a favourite setting for this kind of story – one only has to think of the woods of Ariosto or Tasso, or indeed Dante’s selva oscura – and which Amadis addresses in the Act 2 air “Bois épais” (dense wood…).

The tragedy turns on the fate of Arcabonne, who is torn between love and hatred – she carries the memory of how she was once saved from certain death by a man whose face she glimpsed but whose name she never knew. Having Amadis in her power at last she gazes upon him and realises that he is the same man that saved her, the unknown saviour whom she has secretly loved all this time…

The tragédie en musique is a very disciplined form of music theatre, almost as much danced as it is sung. This production benefitted from having not only professional dancers but also in a choreographer (Françoise Deniau) who knows something of 17th-century ballet de cour, the theatrical dances that Lully would have known and danced, and from which modern ballet derives. While the choreography didn’t attempt an authentic reconstruction, it nevertheless cleverly blended old and new styles so that the dancers weren’t pushed too far out of their comfort zones whilst embodying the music in reasonable style. Musical authenticity, on the other hand, is completely taken for granted nowadays, and indeed the orchestra under CMBV’s Olivier Schneebeli played beautifully throughout, with wonderful plucked continuo (two theorbos plus lute/ baroque guitar if you please), lovely woodwind playing and a percussionist (David Joignaux) who covered an impressive array of instruments, including thunder effects!

The cast of singers were very good, including unnamed soloists from the chorus, with Dagmar Šašková (Corisande), Alain Buet (Arcalaüs) and Isabelle Druet (Arcabonne) especially strong. Haute-contre Cyril Auvity (Amadis) has begun to carve out a career in this repertoire, and his experience certainly showed, though I couldn’t help being concerned at the strain that came through occasionally in the upper register, as well as an occasional looseness in delivery, though his voice at its best is certainly as sweet as ever.

Olivier Bénézech’s production created a clear frame for communicating the narrative, both as sung and as danced theatre. Graphic projections onto the backstage suggested settings in a way that followed the original text whilst suggesting modern analogies, but instead of playing with aesthetic conceits this production helped make this old story clearer, inviting us to engage with it even more closely. I can see why contemporary audiences returned to see these works again and again, and certainly wish that I could have done the same.

Considerably well executed blog post…